Counter-intuitive statements call for clarification.

Check out these subjects on this page:

> Lower load, lower revenue and still higher profit?

> Why is there a natural cap on load factors?

Back to the main article.

|

|

Counter-intuitive statements call for clarification.

|

In most markets, a -close to- 100% load factor is not a realistic target. Open markets fluctuate and available capacity sets and upper end to that fluctuation.

That is because if capacity were to limitlessly fluctuate along with demand, resources like fleet, crew, airport staff and facilities would stand by most of the time waiting for the peaks. The price of such under-utilization is very high.

So airlines have to fill flights at shoulder times too. However, the possibilities to do that will be restrained by the capacity at peak times.

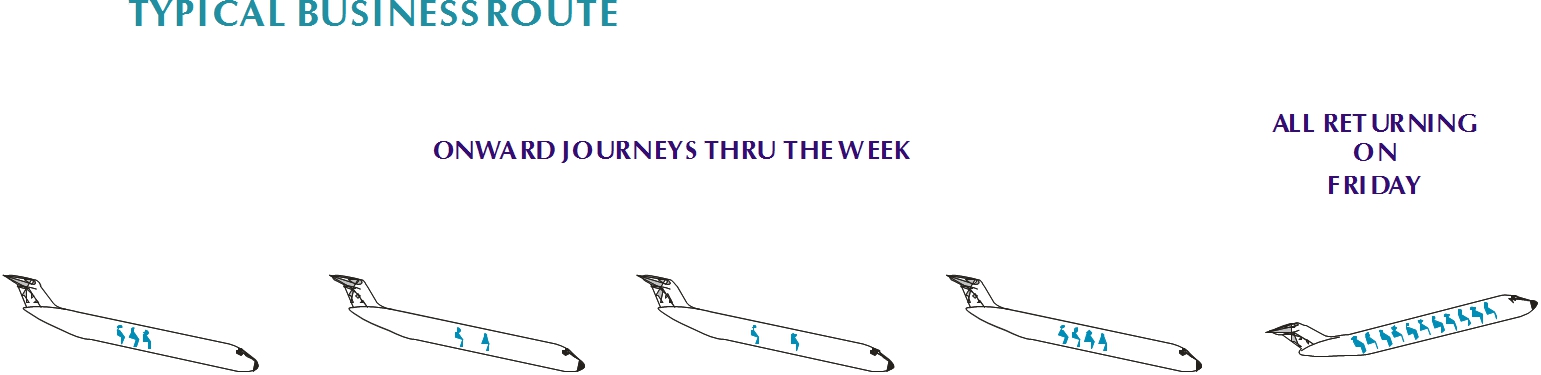

A typical example illustrating this, occurs on any business route as depicted below: the Friday afternoon flights will fill up easily, but after running out of return seats at that popular moment, selling out the Tuesday-Friday morning onward flights becomes a more uphill battle.

Of course, not everyone will travel according to such pattern and not all markets have the above structure.

However, the vast majority of markets, whether it concerns holiday charters, cargo, low cost or ad-hoc, has some kind of prefered timing, not rarely all coinciding on the calendar.

Marketing departments pull all tricks to attract complementary segments but it’s just a fact that all flights can never be 100% full, whatever we do.

From a strategic perspective it’s even questionable to want this, because selling “No” too often, will open the door for opportunistic competition on that Friday flight.

Back to the main article.

The differences between clients can be huge. Everybody knows how neighbouring passengers may have paid widely different amounts.

Yet, even with much smaller fare differences, airlines are in tricky territory when optimizing revenues. It's is not always the same as optimizing company profits.

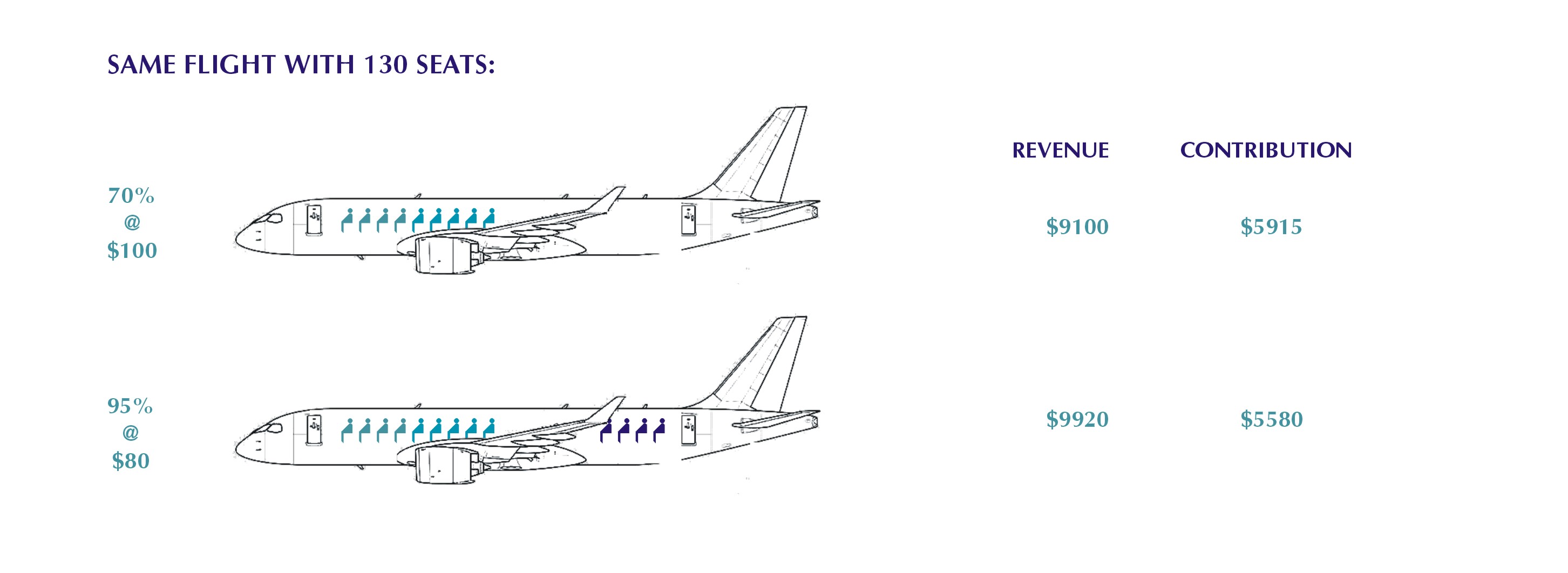

The following example shows how a 70% load can have a higher contribution to profits than a 95% load in that same market.

For the sake of simplicity, we've assumed a lab-situation with two market segments: One that will accept a fare of $80 and one that would accept a fare of $100, and we feature one constant fare for the flight.

Out of 130 seats, the $100 segment would fill 91 seats, while stimulating the market with a price of $80 instead, would attract some 33 passengers more.

The maximum revenue would be $9920, to be achieved with the lower price.

So from the perspective of optimizing revenues, the $80 will be the right fare for this market. It generates 9% more revenue.

However, traffic related costs are $35 per passenger. Looking at the contribution to profits, only $5580 of this $9920 remains for the company to cover other operational and fixed costs.

With the higher fare and lower load, this amount will be $5915, which is 6% more.

So in this case stimulation does indeed work to achieve a higher revenue, but company profits will be better off with a lower revenue and a lower load.

Of course, every day's practice is more diffuse but these numbers are realistic and the fundamantal dynamics in this example play out all the time.

Optimizing on contribution can save a lot of money!

Back to the main article.